Fredy Massad el

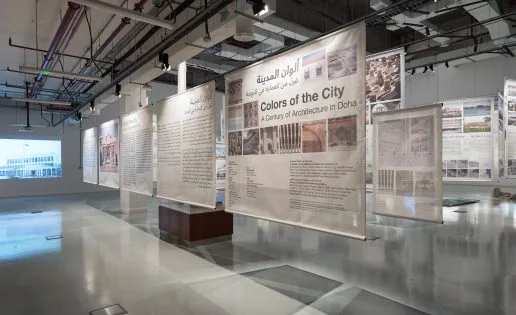

Colors of the City: A Century of Architecture in Doha is a dual-themed exhibition that explores the city’s architectural evolution in response to global influences. It is part of the programme of Design Doha, a new design biennale organised by Qatar Museums, and which will be a showcase for excellence and innovation in the design community of Qatar and the MENA region. The exhibition was envisioned by Glenn Adamson, artistic director of Doha Design, who wanted to supplement the exhibitions featuring contemporary talent in the region with a show devoted to the specific local history of the city and its architectural landscape. The art and architecture historian Péter Tamás Nagy has been in charge of curating this exhibition tracing the architectural history of Doha through a variety of styles including “Arabic Deco,” Doha Classicism”, and Qatari adaptations influenced by Euro-American and Indian styles, as well as the era of Brutalism. The second section of the exhibition looks at Ibrahim Al Jaidah’s projects, such as the Al Thumama stadium for the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022, demonstrating how his designs harmonise cosmopolitan and regional heritage elements. Through 3-D models, photos, interviews, and film, Colors of the City threads its way through Doha’s architectural fabric, revealing the remarkable architecture built before the meteoric development that transformed Doha into a paradigmatic 21st century capital.

How did you become interested in Qatari architecture in the first place?

Qatar Museums is the state authority responsible for restoring and activating heritage architecture in the country, and about three years ago, they were looking for somebody to undertake content research on the buildings. I recently finished my PhD when they reached out to me. My education focused on the history of Islamic art and architecture, which (I must admit) did not cover anything directly related to Qatar: this was new for me. When I had my first conversations with QM as part of the recruitment process, we came up with potential research subjects, and those have been evolving and expanding ever since. What is particularly stimulating is that, in comparison with most other countries, so little work has been done in the field that one can quickly discover new information.

How did you translate this research into an exhibition?

That was indeed the crucial challenge: researching, curating, and designing had to develop hand in hand. My previous experience was chiefly in writing academic papers. Now, I needed to find a way to present the (still incomplete) content in an exhibition. The result strongly reflects my background. Some visitors have noted that Colors of the City appears like an exhibited study rather than something conceived by a curator – they are quite right.

The content research continued during the curating process while I gradually communicated my progress to the exhibition designers, namely Karl Bassil and Carla Khayat, from Mind the gap agency. We shared many exciting (and exhausting) times working closely together, often long hours into the night. They are well-accomplished and experienced exhibition designers – also blessed with stoic patience to endure my shortcomings – and thus closely assisted me in transforming the narrative into a physical display. It was a tough challenge and a steep learning curve, but their commendable expertise somehow (indeed, nearly miraculously to me) allowed us to pull it off. Additionally, the production company Interspace has done an impeccable job within an arguably world-record timeframe.

Who were the first international architects involved in the process of constructing modern Doha?

This is an exciting question, one that forms the core of my research. Consider the challenge: documentary evidence from the 1950s–1960s, such as contracts or architectural drawings, is nearly nonexistent. In the absence of such sources, I adopted the simple approach of an art historian. By searching for analogies in the buildings’ structural, decorative, and technical features, I was able to formulate hypotheses about the origins of the architects or master builders who worked in Doha.

From December to January, I undertook fieldwork in India because the phenomenon of Doha Deco finds its most apparent analogies with buildings there. Art Deco became prominent in India in the 1930s and remained so all the way to the ’60s, often incorporating vernacular elements in its repertoire. This long chronology is important because, by the time it appeared in Doha in the mid-’50s, Art Deco was out of fashion in most other parts of the world. And given the similarities that one can point out between buildings in South Asia and Doha, I am convinced that most architects (or master builders) came from there. Hence, Colors of the City displays 120 pictures of Art Deco buildings from India and Pakistan. But this is only one chapter of the story.

At about the same time, architectural decoration in Doha occasionally applied Classicist motifs, especially vases and tendrils. Although Neoclassicism was very popular in various parts of the world back in the 19th century, by this time, it was chiefly outdated, except in Iran, where many buildings applied decorations following Classicist design and also incorporating local elements. Many of these features then resurfaced in Qatar. The analogies indicate that Doha Classicism can be attributed to Iranians who, just like Indians, came to the country in this period. We also have an oral history testimony by Yusuf Al Zaman, who recalls an Iranian artisan working on their house’s portal when they heard about the assassination of the American President John Kennedy (that is, late November 1963). Although this gate no longer survives, we have at least one old picture recording its colorful Classicist ornaments.

In sum, while we may not know the architects by name, we can at least trace their origin to South Asia and Iran. The State Hospital of Doha, completed in 1956 and designed by the British architect John R. Harris, stands as a notable exception to this pattern.

Examples of Brutalist buildings are featured at the exhibition. Aside from this style, was there any attempt to build in the “international Modern” style?

Yes, absolutely. Although we decided to call the third section of the exhibition Doha Brutalism (highlighting the Brutalist aspect of some of the buildings), Doha Modernism would have been an equally justifiable title. I hesitated for a while. The buildings exhibited in this section date to the 1970s and the 1980s, and we know the architects who designed them thanks to the surviving documentary evidence from this period. For example, the American architect William Pereira designed the Sheraton Hotel. Another example is the Gulf Cinema by an Iraqi architect, Rifaat Chadirji; then came the Ministry of Interior Affairs by the Lebanese William Sednaoui. The list could go on… What matters more is that they were all renowned architects and part of International Modernism. Our choice to label this section Brutalism resulted from an admittedly impressionistic take from some of the key landmarks.

Which are the buildings do you consider more remarkable from this period?

One of the most iconic buildings from this period is Qatar University. It is a gigantic campus, the first one in the country, completed in 1985. I find it a particularly successful work because the Egyptian architect Kamal El Kafrawi studied the region’s vernacular heritage and decided to focus on the wind tower. Most structures constitute octagonal modules amassed alongside one another, each with a wind tower on top. These are not only decorative but also functional, creating ventilation by channeling the air into the building, meaning they work as passive air-conditioning systems. Most other architects sought to incorporate vernacular elements into their design at the time, but Qatar University seems outstanding, whether aesthetically or functionally.

Being conceived by architects belonging to the Pan-Arabic world, are there any connections between the architecture being built in Qatar and the neighbouring countries and main capitals (such as Baghdad, Teheran or Beirut) or does Qatar represent a very specific case?

There are many similarities, not only because some architects came from other Arab countries but also because international trends were shared commodities. While working on the exhibition, I had the pleasure of learning from the Palestinian architect Hisham Qaddumi, who was a special advisor to the emir and head of the Technical Office of the Amiri Diwan, essentially supervising most state projects in the ‘70s and ‘80s. He recalls that the Technical Office set it as a fundamental requirement to incorporate vernacular, whether Qatari or Islamic, elements into the architectural design. For instance, as mentioned before, Qatar University reinvented the historical wind tower in a pronouncedly modern form.

Perhaps an even better example is the new wing of the Amiri Diwan, completed in 1988. Hisham told me that many architects submitted proposals for this project, but the Technical Office kept rejecting them on the grounds that they failed to convey local significance. As a result, the project was delayed until the Technical Office – a group of about seventy people – eventually came up with a concept that the emir himself found satisfactory. At first sight (and from a distance), it looks like a Brutalist building, severe and rough. Yet, moving closer, one can make out various decorative details following the configuration of gypsum carvings dating back to traditional architectural decoration in Doha. The interior design, shining in lavish marble revetment, features intricately painted and carved wooden panels of Moroccan craftsmanship specifically commissioned for the building. And this, I think, at least partially answers your question regarding links with other countries in the region.

Ibrahim Al Jaidah is featured as the bridge between modern architecture and contemporary architecture. Is his Al Thumama Stadium a vindication of local architecture vs. architecture produced by foreign architects?

In short, yes. Ibrahim Al Jaidah is considered both an architect and an authority on Qatari heritage. The basic concept of Colors of the City was that his career would create a bridge between the two parts. He studied many of the buildings that appear in the first part, while the second part is dedicated entirely to his accomplishments as a designer and CEO of the Arab Engineering Bureau. I am immensely grateful for his contributions, allowing access to his personal and professional archives and lending us various objects.

We also conducted an oral history interview with him, in which he described how, since childhood, he had developed an interest in traditional and early modern buildings in Doha. When he began his professional career around 1990, he took inspiration primarily from traditional architecture, which visitors can easily spot in the exhibited building models. At the same time, he began photographing early modern buildings in Doha, many of which have disappeared since. His most recent book presents invaluable documentation of those.

Regarding the Thumama Stadium, it is definitely of crucial importance not only to Ibrahim but also to Qataris in general, as it is the only stadium in the country designed by a local architect. And the shape follows that of the traditional cap, the taqiya. (Although, now that I think about it, this is not the only stadium in Qatar inspired by vernacular heritage: the Bayt (‘tent’) Stadium in Khor is another example.) I agree that Ibrahim’s accomplishment with the Thumama Stadium vindicates the significance of local design; hence, Colors of the City dedicates a place of pride to its model.

Is it possible to identify among the most contemporary generations of local architects some individuals who are interested in retrieving the legacy of Qatari architecture?

Although I’m not an architect, my general impression is that this question primarily depends on the patron. If they wish to commission a building that has nothing to do with Qatari heritage, the architect should be able to deliver just that. Conversely, I would argue that no matter where the architect came from, they have the chance to assess local heritage before starting to draft their design. There are gifted designers like Hisham Qaddumi and Ibrahim Al Jaidah, who have commendable expertise, indeed the local heritage at their fingertip, and there are also ‘outsiders’ who make an effort to understand Qatari culture. The best example that comes to mind is the National Museum, designed by Jean Nouvel, a French architect. The way he carried out background research is exemplary, in my view. It took almost a decade and a half to complete the project, closely collaborating with the commissioners (the royal family) to create a building that would be meaningful for the locals while constituting a futuristic landmark. His inspiration from the desert rose was very ambitious, seeking to elevate this form into a symbol with a new semantical layer, that of a national symbol.

As long as architects have the resources and time, they can certainly contribute to redefining the architectural language for the 21st century. This last point also means that the more research on Qatari heritage is available, the more contemporary designers can expect to be inspired by that knowledge. Without detailed and academically solid studies of the past, constructing the future would rely on shaky ground.

Doha is a paradigm of the 21st century city. Do you think that this architectural legacy will be able to stand and resist the voracity of real state and the greedy desire for outstanding icons?

This question is relevant anywhere in the world. Is there a common benefit of preserving heritage? My answer is affirmative, but if so, can we succumb to the commodification of heritage for commercial investments? In some cases, this seems to be the only viable solution.

Our mission, as Qatar Museums, is to protect local heritage as authentic as possible, and my standpoint is that everything presented in Colors of the City is worthy of that protection. The old-fashioned perspective maintains that ‘heritage’ equals ‘old’ (essentially pre-1950), and only recently has early modern architecture started to be recognized as well, which is something we are striving to achieve and expand. The general view is now on the brink of changing, and I hope the exhibition might constitute an impetus in that direction. We’ve wished to show people how exciting these buildings are and why they deserve to be safeguarded, restored, and listed as cultural heritage. Yet, I’m painfully aware that some of the exhibited buildings standing today will not exist by the time we celebrate the next Design Doha Biennial in two years.

Images: (c) Julián Velásquez, Courtesy Qatar Museums

CríticaEntrevistasOtros temas

Fredy Massad el